The History of W & J Tod Boatbuilders,

Ferrybridge Weymouth, UK

By Lewis White

(Click on any Picture To View a Larger Version)

Bill and Jack Tod were the two sons of a clergyman who lived in Dorset, a southern county of England in the early 20th Century. It was there that they first started building and selling small wooden boats. The story goes that they were asked to build a 19-foot boat which was agreed upon by the would-be buyer. When the boat was completed, it turned out to be so popular that it became their standard length for many years.

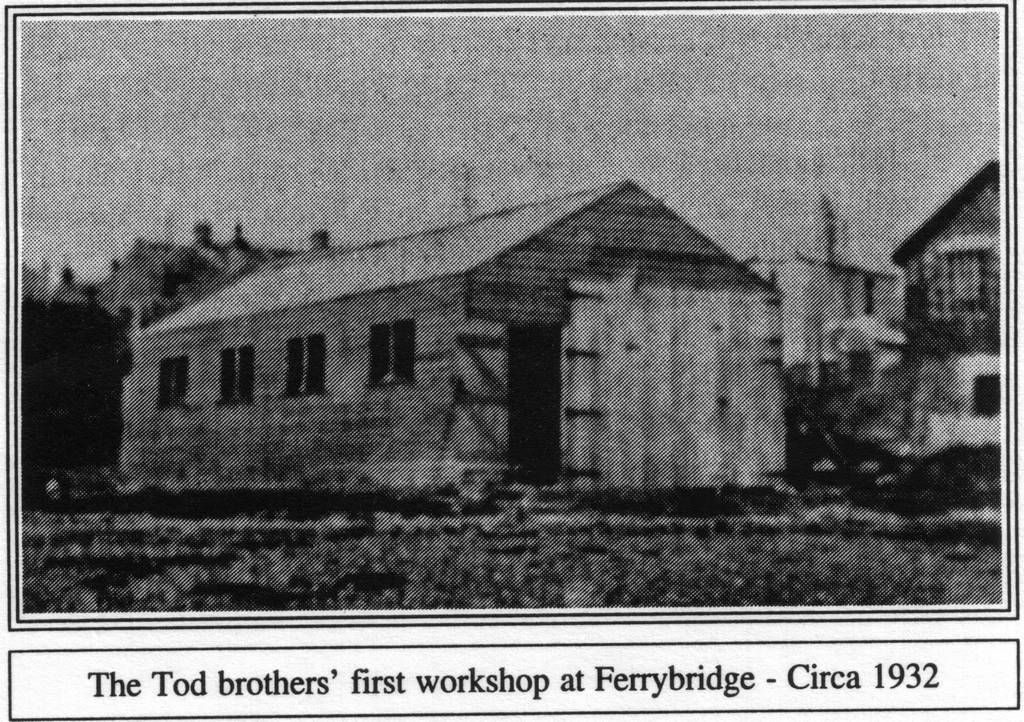

In 1932, they wanted to construct a bigger boat, but their premises at Glanvilles Wooton were too small. So they decided to move temporarily to the shores of the Fleet at Ferrybridge.

Their very first workshop was a simple hut, but when they were asked to build a second, larger craft, the Tod brothers decided to remain at Ferrybridge and extend their workshop.

The workshops were built on land at the edge of the shoreline and it was sufficiently dry and firm to enable them to erect a second, more substantial building.

The business grew quickly and Bill and Jack began to employ local craftsmen to help build the boats.

They also decided to move their families down to Wyke Regis where they built small wooden bungalows to live in.

The brothers made a reasonable living but like most small business, it reached the stage where a considerable infusion of capital was required if they were to further expand and prosper. Neither Bill nor Jack had the necessary funds and neither was particularly enthusiastic about the managing of the commercial side of the business, preferring to concentrate on the more interesting engineering and design aspects. Just before the Second World War in 1938, Mr. Norman Wright came on the scene and put the required capital into the company and gradually assumed overall control. Soon thereafter, another building was added.

Bill and Jack stayed with the company for a number of years, throughout World War II.

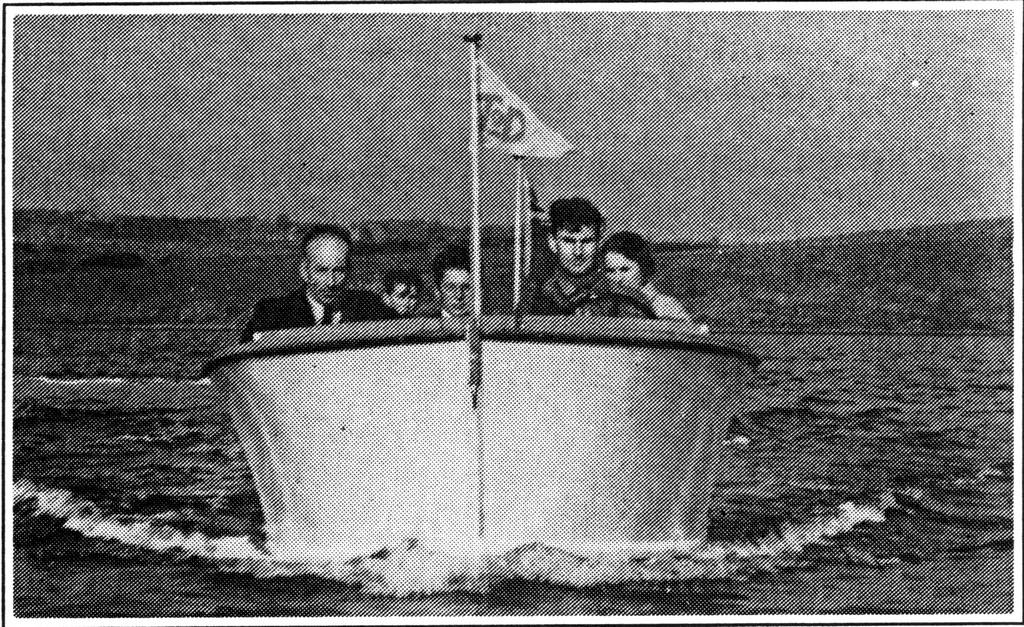

The Tods are seen enjoying a family trip in the early part of the 1939. Around that time a few different types of boats were built.

In 1939, World War II was imminent and the Admiralty soon began to purchase the well-crafted 19-foot Tod boats and they rapidly became the standard admiralty specification for such boats. During the war, the facilities and the company were expanded to enable the firm to build not only boats but a whole range of other components in wood and metal.

One of the strangest jobs carried out for the Admiralty was to build a full-sized dummy submarine of the S Class, built from the waterline up. It was complete down to the finest detail, with a gun, conning tower, periscope and all accessories constructed of timber throughout, and 212 feet long.

It was launched in great secrecy in 1940 and anchored in Portland Harbor, an apparently noble addition to Britains mighty fleet.

The only odd thing about the grey painted craft was that it bobbed up and down in the water when it was choppy. It did of course do the job it was intended to do, and that was to attract the aircraft of the German Luftwaffe that continued to bomb and gun the unsinkable submarine over a considerable period of time. There were times when repairs had to be carried out to continue making it look authentic until finally a direct hit reduced it to matchwood.

About 200 craft of all sizes were launched from Tods boatyard during the war years. There were 16-foot survey craft for use along enemy-occupied coasts and for locating minefields. There were also small, fast motorboats known as sea jeeps carried by destroyers, cruisers and battleships; 25-foot motorboats, both petrol and diesel driven; and 36-foot harbor launches used for landing stores and men from larger ships. Two assault landing craft, powered by twin V8 engines were also built. These were constructed of wood, but clad with armor plating, and they saw considerable action in Norway, Sicily and the Lofoten Islands.

Tods also made floating skids or ducks to combat magnetic mines. They were about 40 feet square and fitted with a massive 8-ton copper wire coil. They were towed by a cable approximately 400 yards long behind a degaussed trawler.

With the Whitehead Torpedo Works situated across the street, the Ferry bridge area became a focal point for enemy air raid attacks and on many occasions the workers had to dive for cover as the German aircraft flew overhead, machine gunning and dropping bombs.

In 1941, the Torpedo Works suffered severe damage but the small Tod boatyard survived unscathed and with no casualties. The wartime workforce never exceeded 40 workers, eight of whom were women.

At Tods, not a single piece of wood was wasted. All timber parts were cut from planks to a set pattern and then stored ready for use. Any sawdust was drawn off by a suction pump direct to a furnace which helped provide central heating fro the workshops.

In June 1944, a heavy bomber with a crew of ten returning from a raid over France was seen crashing in the sea about three miles from the Tod works. Jack Tod had a boat carried over the beach by some of the workers and Jack with three other employees assisted in the rescue of the crew. They were awarded monetary payments by the Royal National Lifeboat Association for their bravery.

During 1946, the last Admiralty contracts of the war were completed and production was switched to high quality wooden craft that were increasingly exported overseas to such countries as Iraq, Persia and the South Americas. Some 80 per cent of the production output was soon being exported.

Shortly after the war, business was scarce and the company diversified into such things as steel waste barges, although the main production was still the standard range of 19 and 25-foot wooden boats.

1948 was the year the author started his apprenticeship, which was for five years. At the time, the youngest apprentice would have to make and serve the tea at the morning break time, collect the empty cups after the break was over, wash up the cups and hang them up ready for the next morning.

The apprentices were well trained in all aspects of boat building from laying down the lines to all forms of construction including carvel, lapstreak, double diagonal, seam batten and plywood; also painting, varnishing, caulking, riveting, joinery and engine installation.

They would also spend six months in the drawing office and be required to attend night classes at the Technical College studying naval architecture three nights a week.

We were also required to build a 10-foot lapstreak boat using only hand tools. The boats had to be perfect in all the construction and finishing. They were inspected by the production manager and any faults had to be corrected to his satisfaction. Each apprentice had to buy all of his own hand tools. The authors weekly wage for the first two years was ten shillings per week and two shillings extra for each additional year up to five years. Therefore, all the authors Christmas and birthday presents were tools! The apprentices routinely worked 48 ½ -hour weeks.

The company took pride in manufacturing all the components required to produce the product range, including machining the rough-cast propellers and rudders, and fabricating the copper fuel tanks. Only the engines were purchased as a finished product.

Seen here is the production line of the 19-foot cruisers built using double diagonal mahogany construction hulls and solid mahogany cabin, decks and interiors.

These photos show cabin jigs with cabins being built; Wood Mill, Paint Shop, and Fitting Shop making copper fuel tanks; propellers being turned and balanced on knife-edged rollers.

Also shown is the managers office with Mr. Wright and the draftsman going over one of the new designs.

A group shot of the crew, including one woman who did all the necessary office work. The author is seated in the front row with all the other apprentices, third from the right.

In 1947, Tods were building quite a few 19 and 25-foot boats. Most were standard hulls with custom interiors.

This is the interior of a standard 25-foot Tarpon Cruiser. These photos were reproduced for the sales catalog. The author is pictured here.

Pictured above is the cockpit of a 19-foot twin-engine cruiser (Ford Engines) all with a beautiful mahogany finish, very near completion

Around 1949, Tods discovered that fiberglass boats were being built in the USA and more information was sought from the US Embassy in London. It was learned that a few US firms were working with glass fibers and resins and were to contacts Pilkington Glass for more information.

This method of construction was quickly appreciated by Tods who, after several costly experiments, pioneered the use of GRP for boat construction in the UK. Their efforts resulted in the marketing of a 12-foot GRP dinghy in 1950.

Tods wooden boats were selling quite well at this time and in February 1952, it celebrated the launching of its 100th post-war 19-foot Cabin Cruiser, powered by a Ford inboard engine.

However, the range of GRP boats was gradually expanded from a 76" lightweight tender to a 15 heavy duty version for commercial use. Many of the boats were fitted for sail or inboard engines.

Tods line of conventional wooden craft was suspended when the building of a 35-foot cruiser was complete.

A line of GRP cabin cruisers were built in sizes ranging from 20 to 28 feet, and were very well accepted.

A number of the 28-foot Tornadoes were entered in the offshore power boat races and did remarkably well when up against some quite larger craft.

Another large project was to build the prototype and 19 additional 37-foot-long lifeboats for the luxury cruiser Oriana for the P&O Line. These were the largest such units in the world, each being capable of carrying 165 passengers. These boats were extensively tested by Lloyds of London, including drop and stress tests.

In 1972, due to the success of producing large commercial moldings, all boat production was phased out, but W & J Tod remains in business today, producing many specialty marine and aerospace products.

Full permission given by Doug Hollings for articles reprinted from his book, "All About Ferry Bridge."